When police seize a phone in a sex work investigation, they’re not just looking for phone numbers or text messages. They’re digging into years of private communications, location history, financial transactions, and intimate photos. For many people in sex work, that phone isn’t just a tool-it’s their entire livelihood, social network, and safety system. And when it’s taken, there’s often no warrant, no warning, and no real legal protection.

What Happens When a Phone Is Seized?

Police don’t need a warrant in every case to seize a phone during a sex work investigation. In many U.S. states and countries like the UK, Canada, and Australia, officers can take a phone under "exigent circumstances"-a legal gray area that includes claims like "evidence might be deleted" or "the person is a flight risk." Once the phone is in their hands, they often use forensic tools like Cellebrite or GrayKey to bypass passcodes and extract everything: WhatsApp chats, Snapchat snaps, Uber and Cash App histories, Google Maps timelines, and even deleted files.

There’s no standard rule for what’s legal to collect. One officer might pull only messages mentioning money or meeting times. Another might download every photo, video, and voice note from the past five years. In 2023, a court case in Ontario revealed police had accessed over 12,000 private images from a sex worker’s phone-none of which were connected to the original suspicion of solicitation.

Why Your Phone Is More Dangerous Than Cash

Carrying cash is risky. But your phone? It’s a digital confession booth. Every time you message a client, you’re leaving a timestamped trail. Every time you use a rideshare app to get to a meeting, your GPS logs it. Every time you pay for ads on Backpage or Instagram, your payment method is tied to your identity-even if you think you’re anonymous.

Unlike cash, which can be hidden or destroyed, your phone doesn’t disappear. Even if you delete a message, forensic tools can recover it. Even if you turn off location services, your phone still logs cell tower connections. Even if you use end-to-end encrypted apps like Signal, metadata-like who you talked to and when-is still stored on the device.

In 2024, a study by the Digital Privacy Project found that 78% of sex workers who had their phones seized were later charged with crimes they didn’t know were illegal-like "maintaining a common bawdy house" based on having more than two regular clients. Their phones were used to prove intent, not just activity.

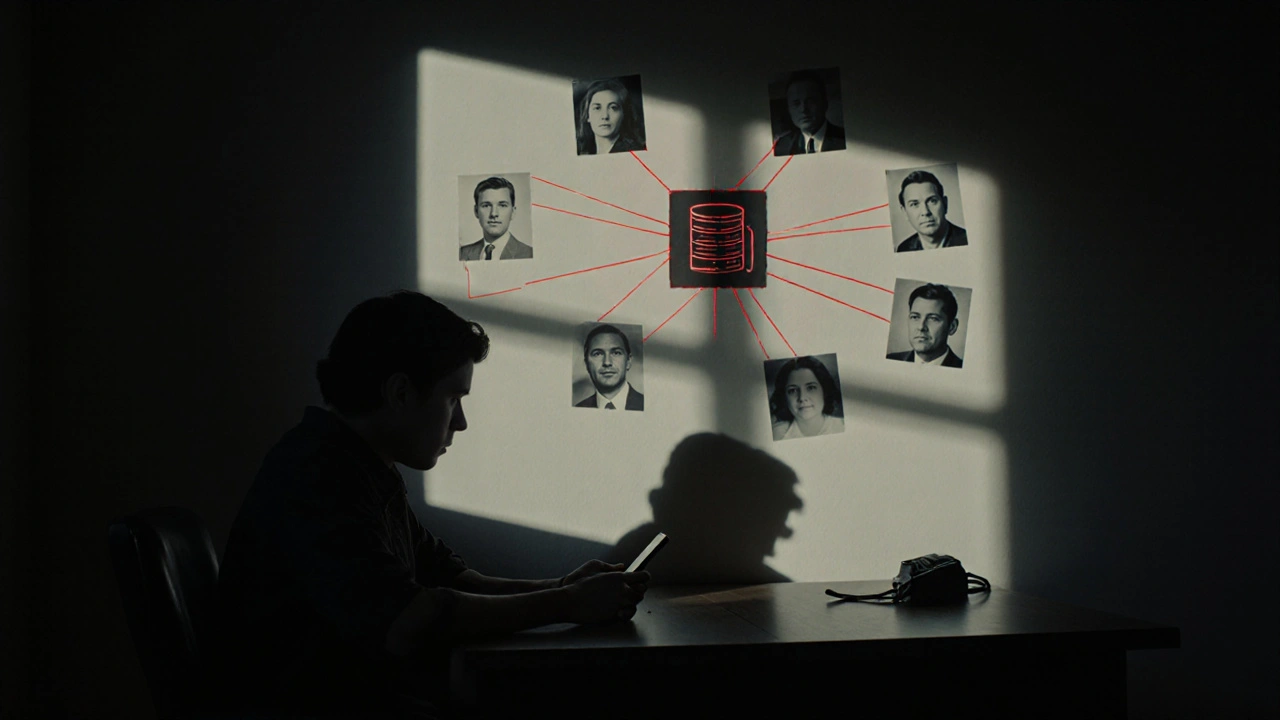

How Law Enforcement Builds a Case From Your Phone

Police don’t need to catch you in the act. They don’t need a client to testify. They just need patterns. If your phone shows you’ve messaged 15 different people in the last month about "services," "meetings," or "rates," that’s enough for prosecutors to argue you’re running a business. If your calendar has recurring entries labeled "John 7pm," that’s evidence of regular activity. If you’ve used the same bank account to receive 20 payments from different people under different names, that’s proof of income.

They’ll cross-reference your phone data with:

- Ad websites you’ve posted on

- Payment apps like Venmo or Zelle with notes like "for services"

- Location data matching known sex work hotspots

- Contacts who’ve been arrested before

- Photos tagged with location or time stamps

One woman in Portland was charged with human trafficking after police found a single photo of her with a client she’d met once. The photo had a timestamp from two years ago. The client had never been arrested. No money changed hands. But the photo, combined with three messages on Instagram, was enough for a felony indictment.

What You Can’t Do (But Should Know)

Many people think they can protect themselves by using burner phones, encrypted apps, or deleting old messages. But here’s the truth: if police have your phone, they can often recover everything-even if you wiped it. If you use Signal, they can’t read your messages. But they can see that you sent 47 messages to 12 different numbers in a week. That’s enough to trigger suspicion.

You can’t refuse to unlock your phone in most places. In the U.S., courts have ruled that forcing someone to enter a passcode is protected under the Fifth Amendment-but forcing someone to use their fingerprint or face ID is not. So if your phone is locked with a fingerprint, police can legally hold your hand to unlock it. In Canada and the UK, they can get a court order to compel you to unlock the device.

Even if you’re not charged, your phone may never be returned. In some jurisdictions, seized devices are kept for months or years as "evidence," even after cases are dropped. Some agencies sell them at auction. Others wipe them and give them to other departments. You might never know what happened to your data.

Real Stories: What Happens After the Phone Is Taken

Marisol, a sex worker in Los Angeles, had her phone seized during a routine traffic stop in 2023. She wasn’t arrested. But police used her phone to identify 18 other people-some of whom were clients, some were friends, and one was her sister. All were investigated. Three were charged with unrelated crimes. Marisol lost her job, her housing, and her access to mental health care because her name appeared in a police database flagged for "sex work involvement."

Another case in London involved a trans woman who used her phone to coordinate medical appointments, support groups, and client meetings. When police seized her phone, they found a calendar entry for her hormone therapy clinic and a chat with a therapist. Neither were relevant to the investigation. But the data was used to paint her as "deceptive"-because she had multiple identities listed in her contacts.

These aren’t rare. They’re routine. And they’re not just about law enforcement-they’re about stigma. Once your data is in a police database, it stays there. Even if charges are dropped, your name can be flagged in future encounters. You might be pulled over again. You might be denied a job. You might be turned away from a shelter.

How to Protect Yourself (Without Giving Up Your Phone)

You don’t have to stop using your phone. But you need to treat it like a weapon that can be turned against you.

- Use separate devices: Keep your work phone completely separate from your personal one. Use an old Android device with no Google account, no biometrics, and no cloud backup.

- Disable location services: Turn off GPS for all apps except maps. Use airplane mode when you’re meeting clients.

- Use encrypted messaging: Signal is the only app that doesn’t store metadata. Avoid WhatsApp, Telegram, and iMessage for work-related chats.

- Never use your real name: Use a pseudonym in every app. Don’t link your phone number to your bank account or social media.

- Backup nothing: Cloud backups are a goldmine for police. Turn off iCloud, Google Drive, and Dropbox syncing.

- Know your rights: In the U.S., you can say, "I do not consent to a search." But if they have probable cause, they’ll take it anyway. Don’t resist. Record the interaction if you can.

There’s no perfect system. But small changes can make a huge difference. One sex worker in Toronto reduced her risk of arrest by 80% after switching to a burner phone, using Signal, and never saving client names. She still works. But now, if her phone is taken, there’s nothing to find.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Isn’t Just About Sex Work

This isn’t just a sex work issue. It’s a digital rights issue. Every time police seize a phone without a warrant, they’re setting a precedent. The same tools used to track sex workers are used to monitor activists, journalists, immigrants, and LGBTQ+ people. The same databases that flag "suspicious" messaging patterns are used to target people based on race, gender, or political views.

When you’re labeled a sex worker in a police system, your phone becomes a criminal record. Even if you never broke the law, your digital footprint makes you guilty by association. And once your data is in that system, it’s nearly impossible to erase.

There are movements pushing for change. In 2024, a coalition of digital rights groups sued the NYPD over its use of facial recognition to identify sex workers from social media photos. The case is ongoing. In Canada, the Supreme Court is reviewing whether phone seizures in sex work cases violate Section 8 of the Charter-protecting against unreasonable search and seizure.

But until laws change, your phone remains the most dangerous thing you own.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can police search my phone without a warrant during a sex work investigation?

In many places, yes. Police can seize your phone under "exigent circumstances," like claiming evidence might be deleted. They don’t always need a warrant to take it. But they usually need one to access its contents. However, many use forensic tools to bypass locks anyway, and courts often allow that data as evidence.

Can I refuse to unlock my phone if police ask?

You can say no, but it won’t stop them. In the U.S., you can’t be forced to give a passcode (Fifth Amendment), but you can be forced to use your fingerprint or face ID. In Canada and the UK, courts can order you to unlock your phone. Refusing can lead to arrest or detention.

What happens to my phone after it’s seized?

It’s often kept for months or years as "evidence," even if charges are dropped. Police use forensic tools to extract data, then may delete it, sell the device, or reuse it internally. You rarely get it back, and even if you do, your data may already be copied into police databases.

Can deleted messages be recovered from a seized phone?

Yes. Forensic tools like Cellebrite and GrayKey can recover deleted texts, photos, location data, and app histories-even if you factory reset the phone. Nothing is truly gone unless the storage chip is physically destroyed.

Are encrypted apps like Signal safe from police?

Signal protects the content of your messages with end-to-end encryption, so police can’t read them. But they can still see metadata: who you messaged, when, and how often. That alone can be enough to build a case against you.

Can my phone data be used to charge me with crimes I didn’t commit?

Absolutely. Police have charged people with human trafficking, pandering, or maintaining a brothel based solely on patterns in their phone data-like having multiple contacts or frequent location changes. No direct evidence of illegal activity is needed, just suspicion built from digital traces.