Imagine you’re leading a group of 12 tourists through the ancient streets of Petra. One moment, everyone’s laughing and taking photos. The next, a woman in her late 60s clutches her chest, turns pale, and collapses. No warning. No time to call for help. This isn’t a movie scene-it’s a real risk every tour escort faces. And if you’re not prepared, seconds can turn into tragedies.

Know Your Group Before You Leave

The best medical emergency plan starts before you even step off the plane. During booking, ask travelers to disclose any chronic conditions, allergies, or mobility issues. Don’t just rely on forms-have a quick chat. Ask: "Do you carry any medications? Any recent hospital visits?" Many people won’t volunteer this unless prompted.Keep a printed list of each person’s medical info: name, emergency contact, allergies, medications, and any known conditions like diabetes, heart issues, or asthma. Store it in your phone and a physical copy in your daypack. Update it if someone tells you something new mid-trip.

One escort in Italy told me she lost a client because she didn’t know the man had a pacemaker. He collapsed during a hike, and the local paramedics didn’t know to avoid using a defibrillator near his device. He survived, but barely. A simple note in her notebook could’ve saved him hours.

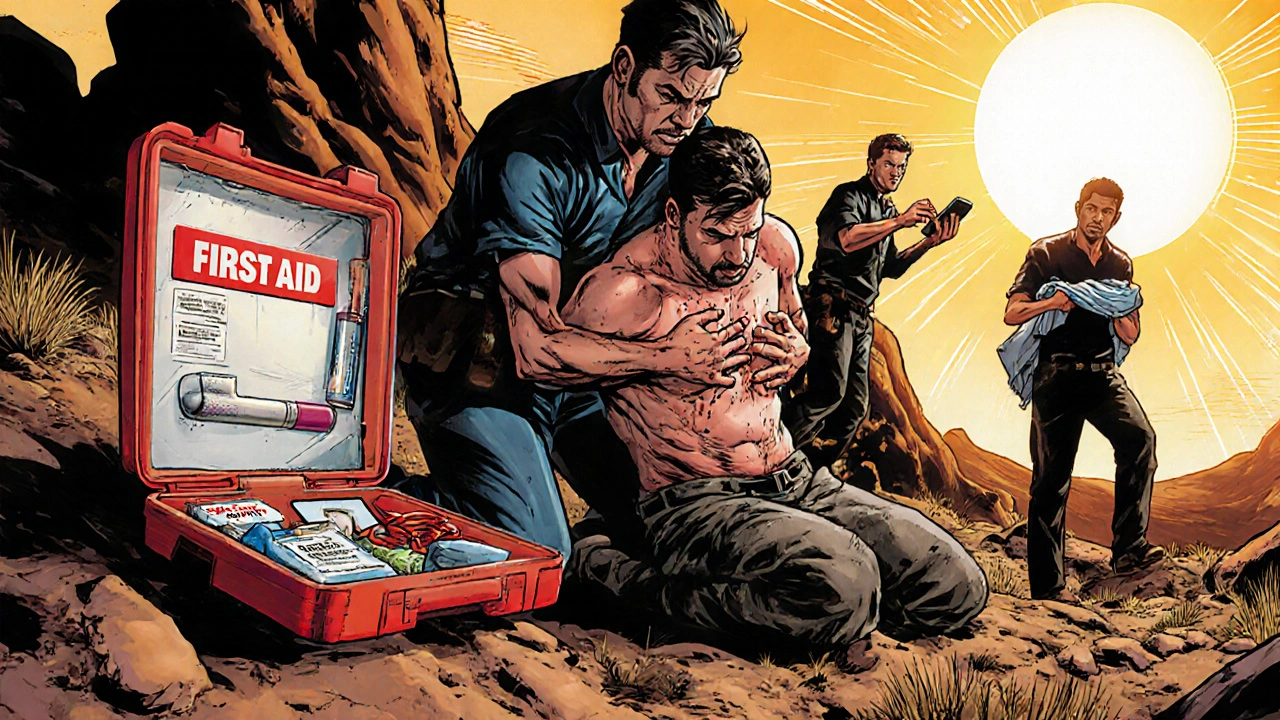

Carry the Right Kit-Not Just Bandages

A basic first aid kit isn’t enough. Tour escorts need a travel-specific medical kit that goes beyond Band-Aids and antiseptic wipes. Here’s what works:- Epinephrine auto-injectors (EpiPens) - for severe allergic reactions

- Aspirin (81mg or 325mg) - for suspected heart attacks

- Oral glucose gel or tablets - for diabetics with low blood sugar

- Antihistamines (like cetirizine or diphenhydramine)

- Nitroglycerin spray (if you’re guiding high-risk elderly groups)

- Thermometer, gloves, face masks, and a CPR face shield

- A small flashlight and a penlight for checking pupils

Don’t carry prescription meds unless you’re trained and authorized. Never give someone else’s pills. But aspirin? In a suspected heart attack, giving one 325mg tablet (chewed, not swallowed) can cut death risk by 20%. That’s backed by the American Heart Association.

Recognize the Top 5 Medical Emergencies on Tour

Not every fainting spell is a heart attack. But you need to tell the difference fast. Here are the five most common medical emergencies on tours-and how to spot them:- Heart attack: Chest pressure or pain that lasts more than a few minutes, radiating to the arm or jaw. Sweating, nausea, shortness of breath. Women often have subtler signs-fatigue, back pain, indigestion.

- Stroke: Use FAST. Face drooping? Arm weakness? Speech slurred? Time to call help. Don’t wait to see if it gets better.

- Anaphylaxis: Swelling of lips or throat, hives, wheezing, sudden dizziness. Happens within minutes of exposure to food, insect stings, or medication.

- Severe hypoglycemia: Shaking, confusion, pale skin, sweating, loss of consciousness. Common in diabetics who skipped meals or overexerted.

- Heatstroke: Hot, dry skin, confusion, rapid pulse, no sweating. Especially dangerous in desert tours or summer cities.

Don’t guess. If you’re unsure, treat it like the worst-case scenario. Better to overreact than underreact.

Act Fast-But Stay Calm

Panic spreads faster than infection. If someone collapses, don’t crowd them. Clear space. Shout for help-ask one person to call local emergency services, another to fetch your kit, a third to get water or a fan if it’s hot.For cardiac arrest: Start CPR immediately. Push hard and fast in the center of the chest-at least 100 to 120 beats per minute. You don’t need to give breaths unless you’re trained. Hands-only CPR saves lives. The Red Cross says 70% of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests happen at home, but tour groups are next on the list.

For anaphylaxis: Use the EpiPen. Inject into the outer thigh. Hold for 3 seconds. Even if symptoms improve, they still need to go to the hospital. Reactions can come back.

For stroke or suspected heart attack: Don’t let them walk. Don’t give them food or water. Just keep them calm and still until help arrives.

Know Local Emergency Numbers-And How to Communicate

In France, it’s 15. In Japan, it’s 119. In Mexico, 911 works in most cities. But here’s the catch: local responders might not speak English. That’s why you need a simple phrase card.Write down these phrases in the local language:

- "This person needs an ambulance. They are having a heart attack/stroke/allergic reaction."

- "They have an EpiPen/aspirin/diabetes."

- "They are allergic to penicillin/peanuts/bee stings."

Use Google Translate offline. Save the audio version. Show it to paramedics. Point to the phrase. Don’t rely on your broken Spanish or French. Time is blood.

Coordinate with Local Medical Services

Before your tour, find out where the nearest hospital or clinic is. Save their number. Ask your hotel concierge. Write it on your itinerary. In remote areas, know the closest medical outpost-even if it’s a pharmacy with a nurse.Some tour companies now partner with travel insurance providers that offer 24/7 medical hotlines. If yours doesn’t, get your own. Companies like Allianz Travel or World Nomads let you call for advice, find English-speaking doctors, and even arrange medevac. Keep the number in your phone and your kit.

After the Emergency

Once help arrives, don’t vanish. Stay with the person until paramedics take over. Then, notify their emergency contact. If they’re alone, offer to stay with them at the hospital or help arrange a family member to fly out.Document everything. Write down the time, symptoms, actions taken, and who responded. This helps with insurance claims and protects you legally.

And after the tour? Debrief. Talk to your team. Did the kit work? Was the response slow? Did you feel prepared? Use that feedback to improve next time.

Training Isn’t Optional-It’s Essential

You wouldn’t drive a bus without a license. Why handle medical emergencies without training? Get certified in CPR and basic first aid. Take a course from the Red Cross, St. John Ambulance, or a local provider. Many offer online modules with in-person skill checks.Don’t wait until after an incident. Take the course now. It takes 4-6 hours. Costs under $100. And in a crisis, it’s the difference between panic and control.

One escort in Bali told me she saved a child from drowning because she’d taken a lifeguard course last year. "I didn’t think I’d ever need it," she said. "Then I did. And I didn’t freeze."

What to Avoid

- Don’t give medications you didn’t bring or aren’t trained to administer.

- Don’t assume someone is "just tired"-especially if they’re over 50.

- Don’t delay calling for help because you’re worried about "overreacting."

- Don’t leave a person alone unless you’re getting help.

- Don’t rely on apps or AI to diagnose. Use your eyes, ears, and training.

Medical emergencies on tour aren’t rare. They’re inevitable. The question isn’t whether one will happen-it’s whether you’ll be ready when it does.

Should tour escorts carry prescription medications for clients?

No. Tour escorts should never carry or administer prescription medications unless they are licensed medical professionals. Even aspirin or antihistamines should only be given if they’re part of your approved first aid kit and the person has consented. Never give someone else’s pills. Always check with the person or their emergency contact before giving anything.

What if a tourist refuses help during a medical emergency?

You can’t force medical care, but you can document their refusal and get it in writing if possible. Say clearly: "I’m concerned you’re having a heart attack. I’m calling an ambulance. If you refuse, please sign this form so we have your choice recorded." If they’re unconscious or confused, assume they need help and act. Legal liability drops significantly if you acted in good faith to save a life.

Are tour escorts legally protected if they help in an emergency?

In most countries, Good Samaritan laws protect people who offer help in good faith. That means if you perform CPR or give aspirin during a suspected heart attack, you can’t be sued unless you acted recklessly or negligently. Always follow basic training guidelines. Don’t try advanced procedures you haven’t been taught. Your intent matters more than perfection.

How often should tour escort first aid kits be checked?

Check your kit before every tour. Look for expired EpiPens, missing gloves, or leaking bottles. Replace anything used-even a single bandage. Keep a checklist: Epinephrine, aspirin, glucose, antihistamines, thermometer, gloves, masks, CPR shield. If you’re guiding in extreme heat or remote areas, add electrolyte packets and a cooling towel. A well-maintained kit is your most reliable tool.

Can a tour escort use a defibrillator (AED)?

Yes-if it’s available and you’ve been trained. Modern AEDs give voice instructions and won’t shock someone who doesn’t need it. If you’re near a public AED (common in airports, train stations, hotels), use it. Don’t wait for paramedics. Every minute without CPR and defibrillation cuts survival chances by 10%. If you’re unsure, follow the device’s prompts. It’s designed for anyone to use.